How Fileless Malware Abuses a Windows Command

An inside look at how attackers exploit %COMSPEC% to silently execute malicious code using built-in system tools.

The Invisible Threat: An Intro to Fileless Attacks

In cybersecurity, attackers are always finding new ways to stay hidden. For a long time, malware was a file that had to be saved on a computer’s hard drive. This left clues that antivirus software could find. But a newer, stealthier method is now common: fileless malware.

Fileless malware doesn’t use its own malicious files. Instead, it uses legitimate programs already on your computer to launch an attack.

This is called “Living off the Land” (LOTL). Attackers abuse trusted Windows tools like PowerShell, Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI), and the Command Shell (cmd.exe) to do their dirty work. Because these are normal system tools, the attack blends in with regular computer activity, making it very hard for traditional antivirus programs to spot. The malware often runs only in the computer's memory (RAM), so when the computer is restarted, all traces can disappear.

What is %COMSPEC% and Why Is It a Target?

Deep inside Windows is an environment variable called %COMSPEC%. Environment variables are system-wide shortcuts that tell Windows where to find important things.

%COMSPEC% has one job: to tell any program the exact location of the Windows Command Shell, cmd.exe.

Programs and scripts rely on %COMSPEC% to run command-line instructions. They trust it completely. This trust is exactly what makes it a perfect target for attackers. If an attacker can control what%COMSPEC% points to, they can trick countless programs into running malicious code without them ever knowing.

Why Does %COMSPEC% Even Exist?

The existence of %COMSPEC% is rooted in the need for stability and backward compatibility. Many programs, scripts, and system processes need to execute command-line instructions as part of their normal operation. Instead of hard-coding the path to cmd.exe and risking failure if that path changes on a future version of Windows or a custom installation, a developer can simply ask the operating system to provide the correct location by referencing the %COMSPEC% variable. It provides a standardized, reliable, and forward-compatible method for finding and launching the command shell.

The Hijack: How %COMSPEC% Becomes a Weapon

Attackers abuse %COMSPEC% in two main ways, a technique classified under MITRE ATT&CK T1059.003

1. The “Bait and Switch” for Persistence : If an attacker gains administrator rights, they can permanently change the %COMSPEC% variable in the Windows Registry. Instead of pointing to the real cmd.exe, they can make it point to their own malware. After this change, any program that tries to open a command prompt will unknowingly run the attacker's malware instead. This gives the attacker a stealthy way to stay on the system, even after a reboot.

2. The “Hidden Hand” for Obfuscation: A more common technique is to use %COMSPEC% to hide a malicious command. This is often seen in attacks that start from a phishing email with a malicious Microsoft Office document. A macro inside the document might run a command like this:

%COMSPEC% /c "powershell -nop -w hidden -enc JAB...VW5pY29kZS5HZXRTdHJpbmco...=="

Here, %COMSPEC% is used to start the real command prompt (cmd.exe). The /c switch tells it to run a command and then close. The command it runs is PowerShell, which is launched silently (-w hidden) and told to execute a long, encoded script (-enc JAB...).

This is a clever evasion tactic. Security software often looks for suspicious process chains, like Microsoft Word (WINWORD.EXE) directly launching PowerShell (powershell.exe). That's a huge red flag. By using cmd.exe as a middleman, the attack chain becomes WINWORD.EXE -> cmd.exe -> powershell.exe. This extra step can fool basic security monitoring and make the attack harder to spot.

Real-world malware, like the Astaroth, Crimson RAT, uses this exact method to execute commands sent from its control server.

Inside the Obfuscated Code

Layer 1: The Command Prompt (cmd.exe) Wrapper

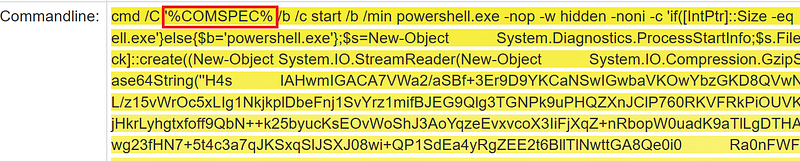

The command begins with:

cmd.exe /c "%COMSPEC% /c start /b /min powershell.exe..."This is a double-layered Command Prompt execution. The first cmd.exe calls another using the %COMSPEC% environment variable. Then, start /b /min is used to launch PowerShell in the background, minimized, and without a visible window.

Why? To break the normal parent-child process chain and confuse monitoring tools. It makes the activity appear less suspicious by disrupting the forensic trace.

Layer 2: The PowerShell Loader

Once PowerShell is launched, it uses several flags:

powershell.exe -nop -w hidden -noni -c ...-nop: No profile (avoids loading user settings)-w hidden: Hides the window-noni: Non-interactive mode

This PowerShell instance receives a long Base64-encoded string as input. Its only job is to decode that string and execute it — but this decoded content is not the final payload.

Layer 3: The Decompression Script

The decoded string from Layer 2 is another PowerShell script. This one contains:

- A second, much longer Base64-encoded string

- A script that uses

System.IO.Compression.GzipStreamto decompress the new string in memory

Why? This is an extra obfuscation layer to hide the final payload from scanners.

Layer 4: The Final Payload

After decoding and decompressing the embedded string, the actual malicious code is revealed.

This final stage:

- Uses

VirtualAllocto allocate memory - Copies raw shellcode into memory using

Marshal::Copy - Runs it with

CreateThread - Uses .NET reflection to dynamically load and execute Windows API calls (e.g.

GetProcAddress)

All of this happens entirely in memory — without writing any files to disk.

Why This Attack Works

- No Files: The entire attack runs in memory. Nothing is written to disk.

- Multi-layer Obfuscation: Uses two layers of Base64 encoding and one Gzip compression layer to hide the real payload.

- Living off the Land: Only uses trusted Windows tools like

cmd.exeandpowershell.exe. - Process Injection: Injects and runs shellcode using native Windows APIs.

- Stealth Execution: PowerShell is launched in hidden and minimized mode.

Fighting Back: How to Detect and Mitigate the Threat

Defending against these stealthy attacks requires focusing on behavior, not just files.

- Aggressive Command-Line Logging: The best way to catch this is to log every command run on your systems, including all arguments. The free Microsoft tool Sysmon is perfect for this. With full logging, you can hunt for suspicious process chains (like

WINWORD.EXE->cmd.exe) and command lines that use%COMSPEC%to launch encoded PowerShell scripts. - Monitor Critical Settings: Use tools to monitor for any changes to the

%COMSPEC%environment variable in the Windows Registry. Any unauthorized modification is a major red flag. - Leverage Modern Tools: Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) platforms are designed to fight fileless malware. They automatically analyze behavior, connect the dots between a suspicious process chain and network activity, and alert you to the entire attack story as it happens.

Final Thoughts

This technique shows how attackers can launch sophisticated, fileless attacks by hiding payloads inside trusted system tools. A single, complex command can bypass traditional antivirus and endpoint protection by avoiding files altogether.

The use of %COMSPEC% highlights a shift toward abusing built-in system components. Defenders must adapt by focusing on system behavior and detecting suspicious process chains that indicate these stealthy, “living off the land” attacks.