Deconstructing the Digital Heartbeat: A Beginner’s Guide to Windows Processes

Every action on a Windows system, from opening a web browser to a background service checking for updates, is organized by processes. To the average user, a process is simply a running program. To a security analyst, however, a process is the fundamental unit of execution and the primary battlefield where malicious activity unfolds. Understanding the anatomy of a Windows process, what it is, how it lives, and how it dies is the first and most critical step in the journey from a computer user to a threat hunter.

The Anatomy of a Windows Process: From Code to Execution

At its core, a process is an instance of a computer program that is being executed. But a more precise and practical definition for an analyst is that a process is a container for the resources needed to execute that program. When the Windows operating system loads an executable file like notepad.exe from the disk into memory, it creates a process to manage it. This process container holds several key components :

- A Private Virtual Address Space: Each process gets its own isolated slice of memory. This prevents one process from interfering with another, ensuring stability. It is within this private space that an attacker will attempt to run malicious code.

- Executable Code: The actual machine instructions of the program are mapped into the process’s address space.

- Open Handles: These are references to system resources like files, registry keys, and network connections that the process is using.

- A Security Context: Defined by an access token, this context specifies the user account the process is running as and its associated privileges. This determines what the process is allowed to do on the system.

- A Unique Process Identifier (PID): A number assigned by the kernel to uniquely identify the process while it is active.

- At Least One Thread of Execution: A thread is the component within a process that actually executes the code. Every process starts with one thread, but can create more to perform multiple tasks concurrently.

Thinking of a process as a container is essential for understanding advanced attacks. Techniques like process injection are fundamentally about forcing a legitimate process’s container to hold and execute malicious code, borrowing its resources and reputation to evade detection.

The Process Lifecycle: A Five-State Journey

A process is not a static entity; it transitions through several states from its creation to its termination. This journey is known as the process lifecycle. While models can vary in complexity, the five-state model provides a clear and comprehensive framework for understanding a process’s status at any given moment.

- New: In this initial state, the operating system has received the instruction to create a process but has not yet fully committed resources or admitted it for execution. The kernel creates a critical data structure called the Process Control Block (PCB), which will store all the attributes of the process, but the process itself is not yet ready to run.

- Ready: The process has been loaded into main memory and has all the resources it needs to execute. It is now waiting in a queue for its turn to be assigned to a CPU core by the OS scheduler. There can be many processes in the ready state at once, all waiting for processor time.

- Running: The process has been selected by the scheduler, and a CPU is actively executing its instructions. On a multi-core system, multiple processes can be in the running state simultaneously, one for each core. A process in this state can execute code in one of two modes: user mode for its own application logic, or kernel mode when it requests a service from the operating system via a system call.

- Waiting (or Blocked): A process enters the waiting state if it cannot proceed until an external event occurs. This could be waiting for data to be read from a hard drive, waiting for a network packet to arrive, or waiting for user input. A process in the waiting state will not be scheduled to run, even if a CPU is free. Once the event it was waiting for completes, the process transitions back to the ready state.

- Terminated: The process has completed its execution or has been terminated by the user or the OS. In this final state, the operating system reclaims all the resources allocated to the process, and its PCB is removed from the system.

The Birth of a Process: CreateProcess And the Parent-Child Relationship

In Windows, most processes are created by other processes, forming a parent-child hierarchy. Unlike UNIX’s fork(), Windows uses the CreateProcess API, which allows detailed control over how new processes are launched. A key security-related option is CREATE_SUSPENDED, which lets the parent pause the child process before it runs—useful for techniques like process hollowing.

Each process gets a unique PID, and its parent’s PID is stored as the PPID, forming a process tree viewable in tools like Process Explorer. This tree is crucial for spotting anomalies.

Some processes, like explorer.exe, appear "orphaned" because their parent (e.g., userinit.exe) exits after setup. This is normal. However, orphaned processes like powershell.exe or cmd.exe are suspicious and may indicate malicious activity. Context is key in determining whether an orphaned process is benign or a threat.

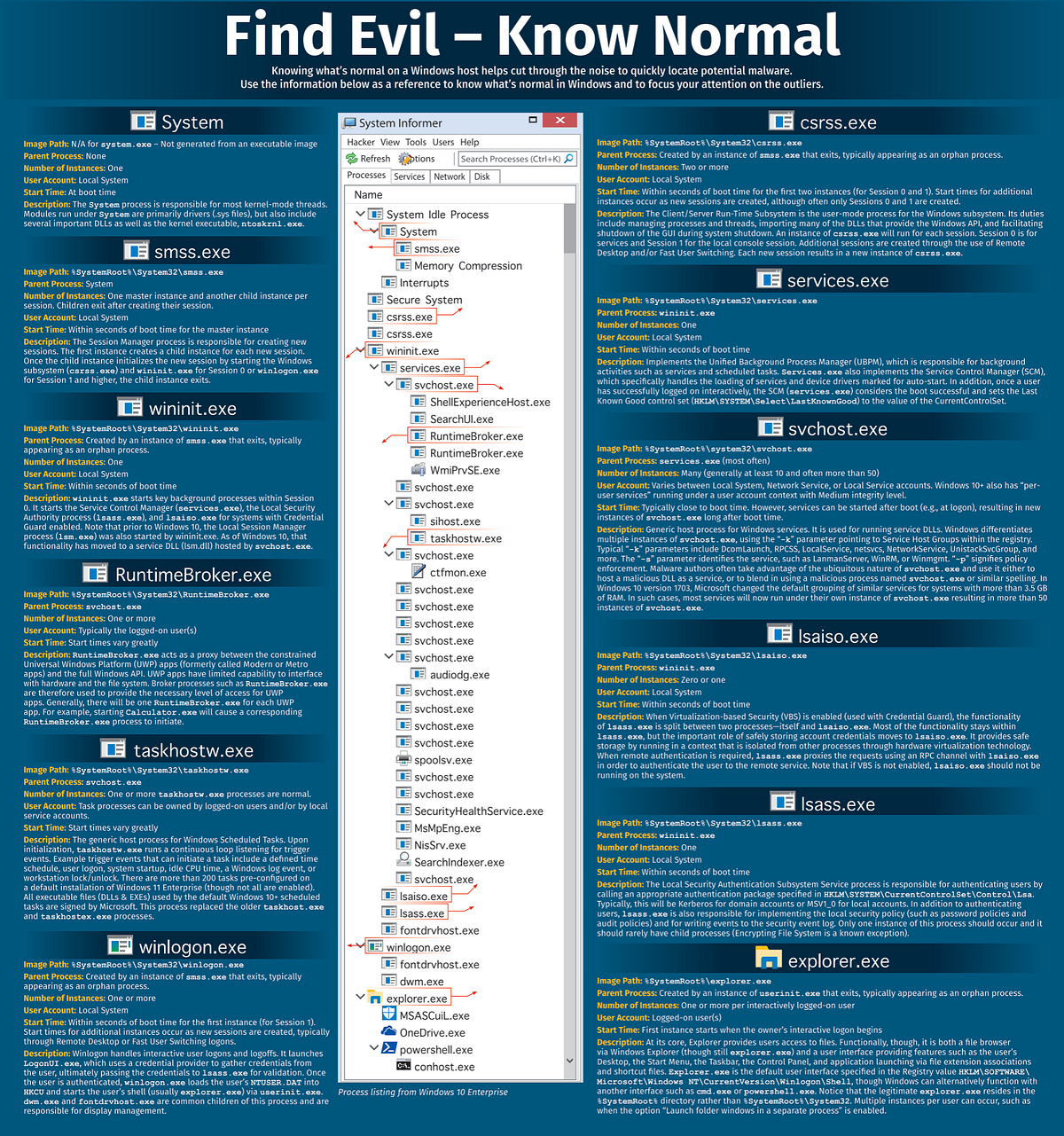

“Know Normal” — The Windows Process Family Tree

The foundational principle of any effective threat hunt is SANS “Know Normal Find Evil”. Before one can identify a malicious process, one must have an unwavering understanding of what constitutes normal, legitimate process activity on a Windows system. Attackers thrive on blending in, masquerading their malware as common system executables. By establishing a baseline of expected processes, their parent-child relationships, their file paths, and the user accounts they run under, an analyst can quickly spot the outliers that warrant investigation.

The Principle: Know Normal, Find Evil

Before detecting malicious activity, analysts must deeply understand what’s normal in a Windows environment. Malware often tries to hide itself by making it look like a real Windows program.

To spot the difference, it’s important to understand things like:

- Which programs usually run

- Which program starts which

- Where are they located on the system

- What user is running them

Windows follows a transparent and ordered process each time it starts. This order helps explain why some programs start other programs (like a parent and child).

System (PID 4): The process tree begins with the System process, which always has PID 4. This is not a user-mode executable that can be found on disk (system.exe does not exist). Instead, it is a special process that hosts the core kernel-mode threads and device drivers (.sys files) that manage the operating system itself. It is the ancestor of all other processes.

smss.exe (Session Manager Subsystem): The first user-mode process started by the System kernel is smss.exe. A single master instance of smss.exe is responsible for creating new user sessions. For each session, it launches a child copy of itself, which then starts the necessary processes for that session before exiting. This is why the processes within a session appear as orphans — their direct parent, the child smss.exe, is gone.

Session 0 (System Services): The first session created, Session 0, is a non-interactive session dedicated to running system services. Here, smss.exe launches csrss.exe (Client/Server Runtime Subsystem) for the session and, critically, wininit.exe (Windows Initialization Process).

wininit.exe and its Children: wininit.exe acts as a key parent process in Session 0. It is responsible for launching three of the most important background processes on the system:

services.exe (Service Control Manager): Manages all system services and drivers marked for auto-start. It is the parent of most svchost.exe instances.

lsass.exe (Local Security Authority Subsystem Service): Handles user authentication, password policies, and security token creation.

lsaiso.exe: If Credential Guard is enabled, this process runs in a secure, virtualized environment to protect user credentials from being stolen from lsass.exe memory.

Session 1 (Interactive User): When a user logs in, a new session is created (typically Session 1). In this session, smss.exe launches another csrss.exe instance and winlogon.exe.

winlogon.exe and the User Shell: winlogon.exe manages the interactive user logon process. After validating the user’s credentials (by communicating with lsass.exe), it launches userinit.exe. userinit.exe performs some final setup tasks (like running logon scripts) and then starts the user’s shell, which is defined in the registry. By default, this shell is explorer.exe. userinit.exe then exits, leaving explorer.exe as an orphan process

“Find Evil” — A Threat Hunter’s Guide to Anomaly Detection

With a solid understanding of what constitutes “normal” on a Windows system, the next step is to develop the skills and learn the tools to find the “evil.” Malicious processes rarely operate in a vacuum; they leave behind a trail of anomalies — subtle deviations from the established baseline. A threat hunter’s job is to recognize these deviations, investigate their context, and determine if they represent a threat.

Common Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) in Processes

When examining a live system or analyzing forensic data, certain characteristics should immediately raise suspicion. This checklist synthesizes common indicators of malicious process behavior:

- Unusual Process Names: This is the most basic indicator. Attackers often use misspellings of legitimate processes to fool a cursory glance (e.g.,

scvhost.exeinstead ofsvchost.exe, orrunndll32.exe). They may also use names that are just a jumble of random characters (e.g.,x7z2y9p.exe). - Anomalous File Paths: Where a process runs from is as important as what it is named. Core system processes have expected locations, almost always

%SystemRoot%\System32. A process likesvchost.exerunning from a temporary folder, a user's profile (C:\Users\...\), or the root of the C: drive is a major red flag. - Unexpected Parent-Child Relationships: The process tree tells a story. An unexpected child process creation by a parent process is a well-known indicator of potentially malicious execution. For example, a Microsoft Word document (

winword.exe) should not be spawning PowerShell (powershell.exe) or the Command Prompt (cmd.exe). This often indicates that a malicious macro or exploit has been triggered. - Unsigned Executables: Most legitimate software from reputable vendors is digitally signed. A digital signature assures the publisher’s identity and that the file has not been tampered with. A process running from an executable that lacks a signature, or has an invalid one, primarily if it’s masquerading as legitimate software, warrants deep scrutiny.

- Suspicious Network Connections: Malware needs to communicate for command and control (C2), data exfiltration, or to download additional payloads. An analyst should look for processes making outbound connections to unknown or suspicious IP addresses. Even more telling is when a process that has no legitimate reason to access the network, such as

notepad.exeorcalc.exe—is observed making network connections. - High Resource Consumption: While not a definitive indicator on its own, unexplained and sustained high CPU or memory usage can be a symptom of malicious activity. For instance, illicit cryptocurrency miners are designed to consume as much CPU power as possible, and poorly written spyware can cause memory leaks.

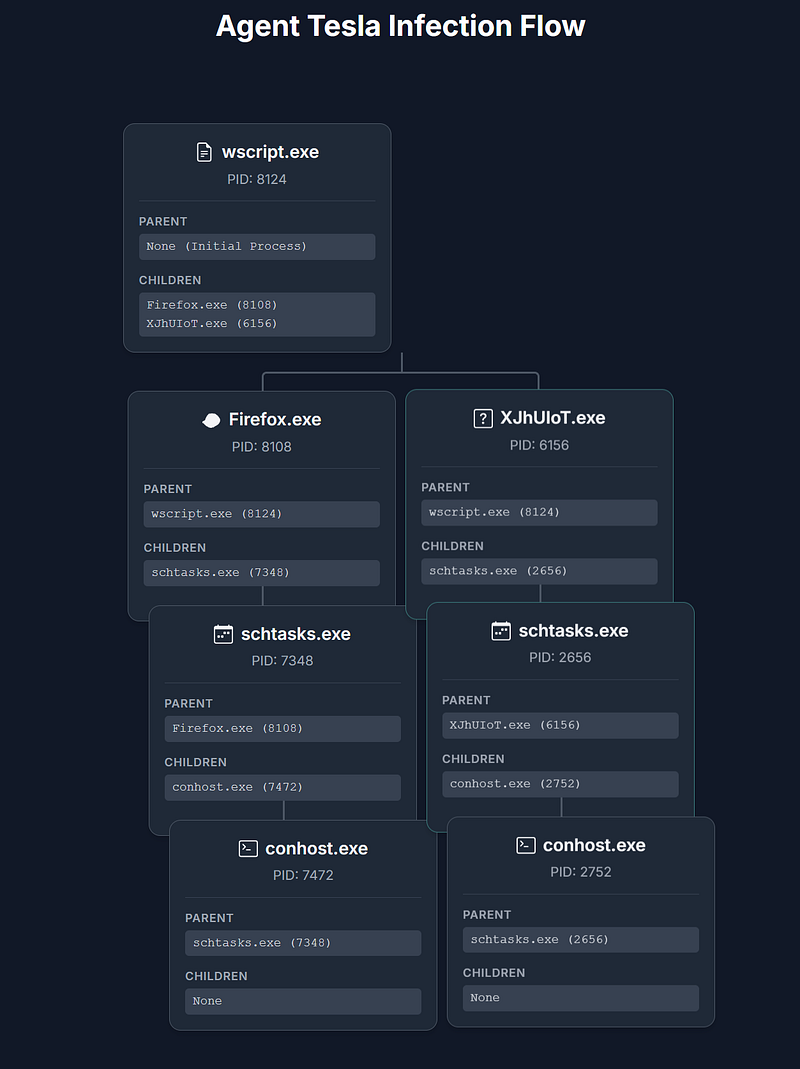

Case Study: Deconstructing an Agent Tesla Infection Chain

Theoretical knowledge is essential, but seeing it applied to a real-world example solidifies the concepts. Let’s deconstruct a malware infection chain involving #Agent Tesla https://www.joesandbox.com/analysis/1751815/0/html

Initial Compromise via Script Execution

The infection begins when the user opens a malicious JavaScript file, in this case, named "Purchase Order_094846.js". This script is executed by the legitimate Windows Script Host.

- Process:

wscript.exe - PID: 8124

- Role: Initial Dropper. This process acts as the entry point for the malware. Its primary function is to execute the malicious script, which then downloads or “drops” the next stages of the malware onto the system and launches them.

Staging and Persistence

Once the initial script is running, it launches two separate processes. These processes are disguised with a common application name (Firefox.exe) and a random name (XJhUIoT.exe) to blend in with normal system activity. Their main goal is not to steal data themselves, but to ensure the malware can survive a reboot.

This is a classic persistence mechanism. The malware uses a legitimate Windows utility, the Task Scheduler, to create tasks that will automatically run the final payload in the future. This is done through two parallel process chains, likely for redundancy.

Chain A:

Firefox.exe(PID: 8108) is launched bywscript.exe.- This stager process then executes

schtasks.exe(PID: 7348) to create a new scheduled task named"Updates\XJhUIoT". The configuration for this task is read from a temporary file in the user'sAppDatadirectory. - The command-line operation requires a console window, so

conhost.exe(PID: 7472) is launched as a legitimate child process ofschtasks.exe.

Chain B:

XJhUIoT.exe(PID: 6156) is also launched by the initialwscript.exescript.- It follows the same pattern, executing

schtasks.exe(PID: 2656) to create a similar (likely identical) scheduled task. - Again,

conhost.exe(PID: 2752) is launched to host the console for the operation.

Summary

The attack demonstrates a sophisticated, multi-stage infection pattern:

- Initial Access: A user is lured into running a malicious script.

- Staging: The script drops stager executables disguised as legitimate software.

- Persistence: The stagers use the Windows Task Scheduler (

schtasks.exe) to ensure the malware will run automatically. - Execution: The scheduled tasks launch the final Agent Tesla payloads to steal and exfiltrate data.

The use of legitimate system tools and a redundant process chain is a key characteristic of this malware’s attempt to remain hidden and effective.

Turning the Tables: Detection and Mitigation Strategies

Understanding how attackers subvert Windows processes is only half the battle. To effectively defend a network, this knowledge must be translated into concrete detection and mitigation strategies. While advanced evasion techniques are designed to be stealthy, they are not invisible. They create subtle but distinct artifacts that can be detected with the proper visibility and a well-tuned monitoring solution.

Conclusion: From Beginner to Hunter

Learning about Windows process analysis can feel overwhelming, but it is based on a simple, strong idea: to find what is unusual, you first need to understand what is normal. The many processes that run a Windows system happen in a clear and predictable way. By getting familiar with this basic setup — the usual process tree, the correct file paths, and the normal user activities — an analyst gains the essential knowledge to understand how the system works.

By combining this basic knowledge with helpful, free tools like Process Explorer, System Informer, and a well set-up Sysmon, anyone curious about technology can start to uncover what is happening inside their system. The journey to becoming skilled begins with one step: creating a test environment, setting up the right monitoring, and beginning to explore. The inner workings of Windows are detailed, but with the right guide and careful attention, they are not impossible to understand.